Welsh Kingdoms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the

Wales was now coming under increasing attack by

Wales was now coming under increasing attack by

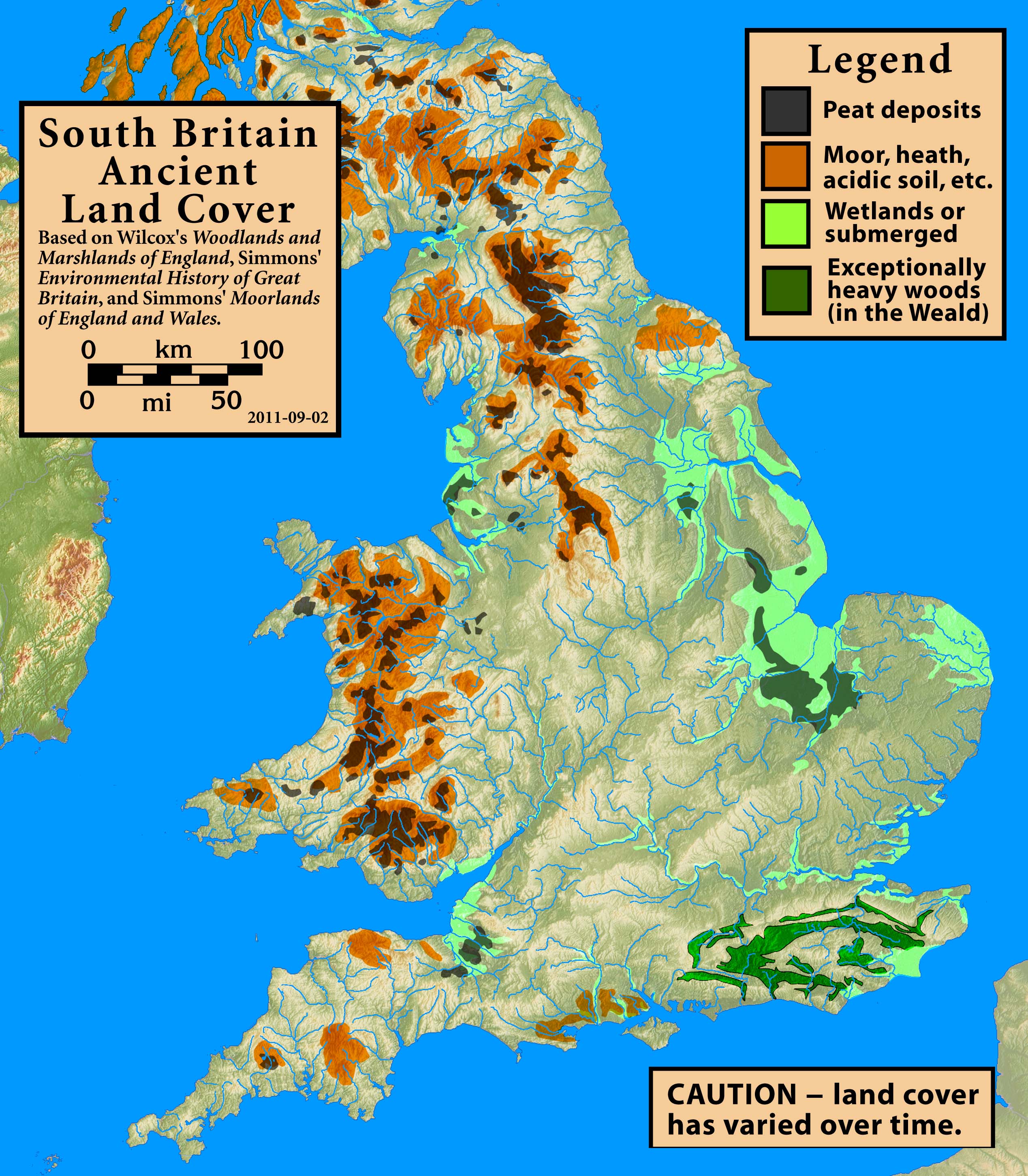

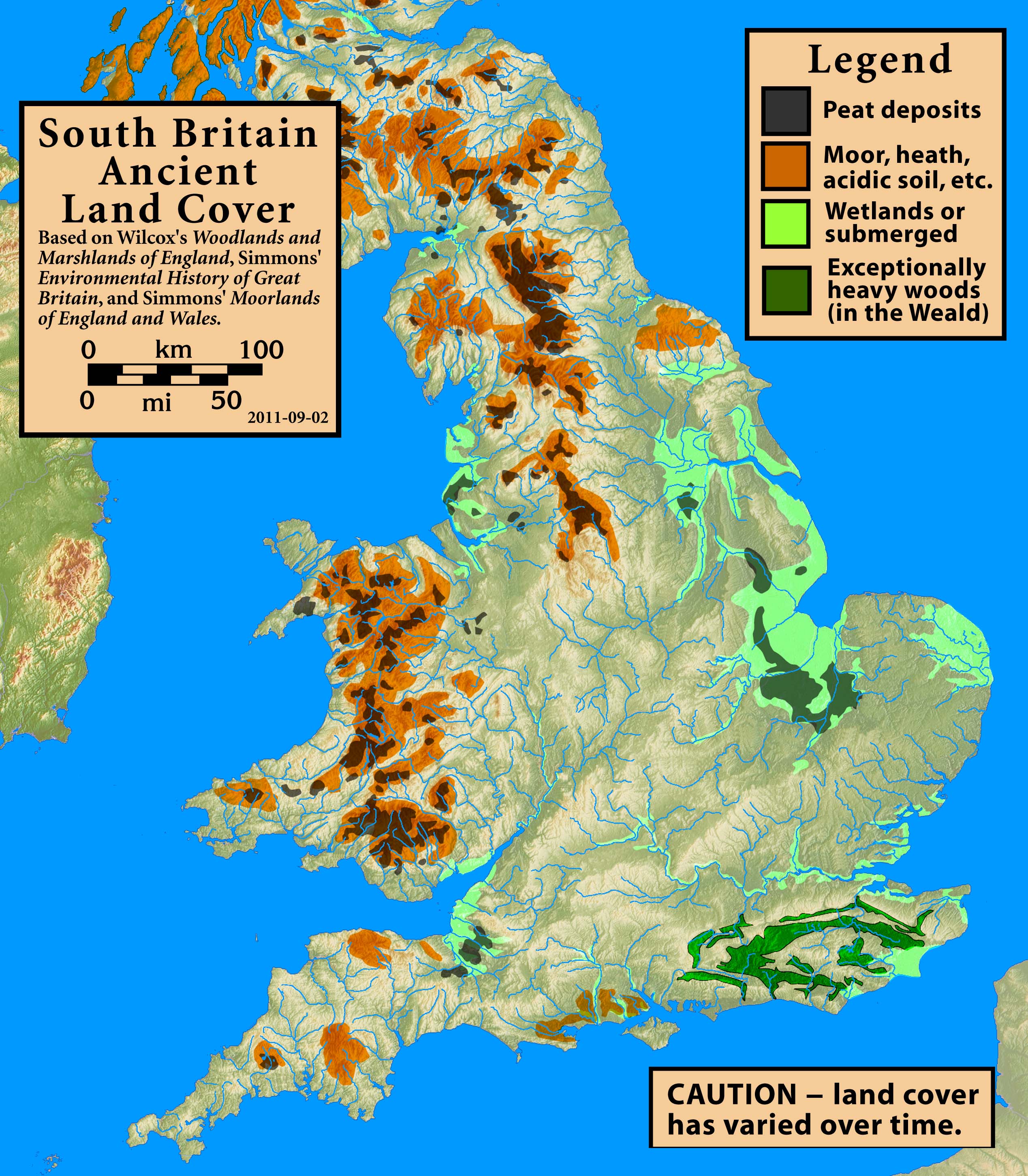

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless

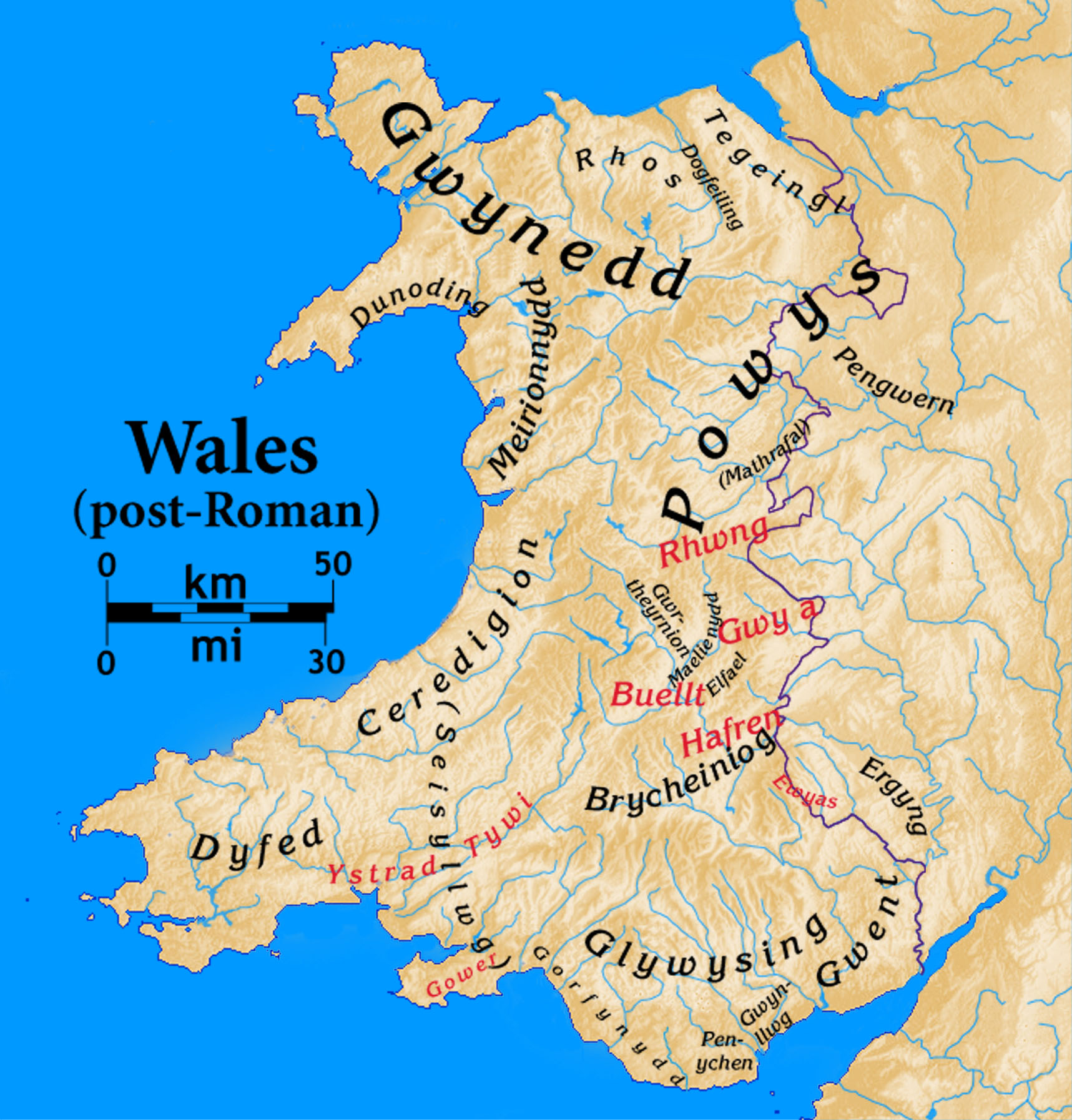

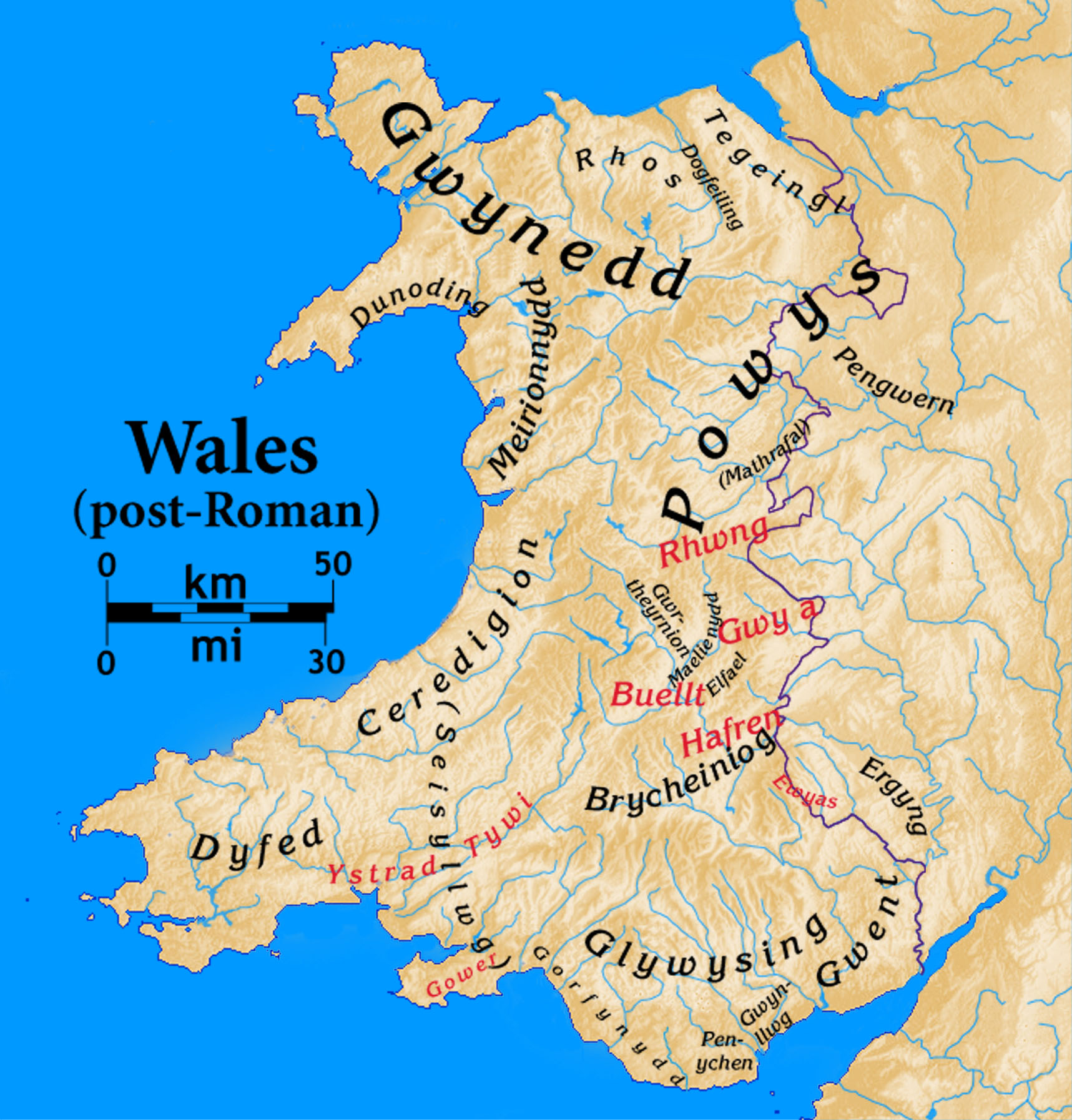

The exact origins and extent of the early kingdoms are speculative. The conjectured minor kings of the sixth century held small areas within a radius of perhaps , probably near the coast. Throughout the era there was dynastic strengthening in some areas while new kingdoms emerged and then disappeared in others. There is no reason to suppose that every part of Wales was part of kingdom even as late as 700.

The exact origins and extent of the early kingdoms are speculative. The conjectured minor kings of the sixth century held small areas within a radius of perhaps , probably near the coast. Throughout the era there was dynastic strengthening in some areas while new kingdoms emerged and then disappeared in others. There is no reason to suppose that every part of Wales was part of kingdom even as late as 700.

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales pages on Early Middle Ages

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wales In The Early Middle Ages .01 Sub-Roman Britain

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

c. 383 until the end of the 10th century. In that time there was a gradual consolidation of power into increasingly hierarchical kingdoms. The end of the early Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

was the time that the Welsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic language family, Celtic language of the Brittonic languages, Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales, by some in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut P ...

transitioned from the Primitive Welsh spoken throughout the era into Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

, and the time when the modern England–Wales border

The England–Wales border ( cy, Y ffin rhwng Cymru a Lloegr; shortened: Ffin Cymru a Lloegr), sometimes referred to as the Wales–England border or the Anglo-Welsh border, runs for from the Dee estuary, in the north, to the Severn estuary i ...

would take its near-final form, a line broadly followed by Offa's Dyke

Offa's Dyke ( cy, Clawdd Offa) is a large linear earthwork that roughly follows the border between England and Wales. The structure is named after Offa, the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia from AD 757 until 796, who is traditionally believed to h ...

, a late eighth-century earthwork. Successful unification into something recognisable as a Welsh state would come in the next era under the descendants of Merfyn Frych

Merfyn Frych ('Merfyn the Freckled'; Old Welsh ''Mermin''), also known as Merfyn ap Gwriad ('Merfyn son of Gwriad') and Merfyn Camwri ('Merfyn the Oppressor'), was King of Gwynedd from around 825 to 844, the first of its kings known not to have de ...

.

Wales was rural

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry typically are describ ...

throughout the era, characterised by small settlements called ''trefi''. The local landscape was controlled by a local aristocracy and ruled by a warrior aristocrat. Control was exerted over a piece of land and, by extension, over the people who lived on that land. Many of the people were tenant peasants or slaves, answerable to the aristocrat who controlled the land on which they lived. There was no sense of a coherent tribe of people and everyone, from ruler down to slave, was defined in terms of his or her kindred family (the ''tud'') and individual status (''braint''). Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

had been introduced in the Roman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

, and the Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point th ...

living in and near Wales were Christian throughout the era.

The semi-legendary founding of Gwynedd in the fifth century was followed by internecine warfare in Wales and with the kindred Brittonic kingdoms of northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

and southern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

(the Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population spo ...

) and structural and linguistic divergence from the southwestern peninsula British kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

known to the Welsh as '' Cernyw'' prior to its eventual absorption into Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

. The seventh and eighth centuries were characterised by ongoing warfare by the northern and eastern Welsh kingdoms against the intruding Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

kingdoms of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

and Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

. That era of struggle saw the Welsh adopt their modern name for themselves, ''Cymry'', meaning "fellow countrymen", and it also saw the demise of all but one of the kindred kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland at the hands of then-ascendant Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

.

History

When the Roman garrison of Britain was withdrawn in 410, the various British states were left self-governing. Evidence for a continuing Roman influence after the departure of theRoman legions

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

is provided by an inscribed stone from Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

dated between the late 5th century and mid 6th century commemorating a certain Cantiorix who was described as a citizen (''cives'') of Gwynedd and a cousin of Maglos the magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

(''magistratus''). There was considerable Irish colonisation in Dyfed in southwest Wales, where there are many stones with Ogham

Ogham (Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langua ...

inscriptions. Wales had become Christian, and the "age of the saints" (approximately 500–700) was marked by the establishment of monastic settlements throughout the country, by religious leaders such as Saint David

Saint David ( cy, Dewi Sant; la, Davidus; ) was a Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century. He is the patron saint of Wales. David was a native of Wales, and tradition has preserved a relatively large amount of detail ab ...

, Illtud

Saint Illtud (also spelled Illtyd, Eltut, and, in Latin, Hildutus), also known as Illtud Farchog or Illtud the Knight, is venerated as the abbot teacher of the divinity school, Bangor Illtyd, located in Llanilltud Fawr (Llantwit Major) in Gla ...

and Teilo

Saint Teilo ( la, Teliarus or '; br, TeliauWainewright, John. in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. XIV. Robert Appleton Co. (New York), 1912. Accessed 20 July 2013. or '; french: Télo or '; – 9 February ), also known by his C ...

.

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

and Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

, who later became the English, were unable to make inroads into Wales except possibly along the Severn Valley as far as Llanidloes

Llanidloes () is a town and community on the A470 and B4518 roads in Powys, within the historic county boundaries of Montgomeryshire ( cy, Sir Drefaldwyn), Wales. The population in 2011 was 2,929, of whom 15% could speak Welsh. It is the third ...

. However, they gradually conquered eastern and southern Britain.At theWales was divided into a number of separate kingdoms, the largest of these beingBattle of Chester The Battle of Chester (Old Welsh: ''Guaith Caer Legion''; Welsh: ''Brwydr Caer'') was a major victory for the Anglo-Saxons over the native Britons near the city of Chester, England in the early 7th century. Æthelfrith of Northumbria annihilated ...in 616 AD, the forces of Powys and other British kingdoms were defeated by the Northumbrians underÆthelfrith Æthelfrith (died c. 616) was King of Bernicia from c. 593 until his death. Around 604 he became the first Bernician king to also rule the neighboring land of Deira, giving him an important place in the development of the later kingdom of North ..., with kingSelyf ap Cynan Selyf ap Cynan or Selyf Sarffgadau (died 616) appears in Old Welsh genealogies as an early 7th-century King of Powys, the son of Cynan Garwyn. His name is a Welsh form of Solomon, appearing in the oldest genealogies as Selim. He reputedly bore th ...among the dead. It has been suggested that this battle finally severed the land connection between Wales and the kingdoms of theHen Ogledd Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population spo ...("Old North"), the Brythonic-speaking regions of what is now southernScotland Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...andnorthern England Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ..., includingRheged Rheged () was one of the kingdoms of the ''Hen Ogledd'' ("Old North"), the Brittonic-speaking region of what is now Northern England and southern Scotland, during the post-Roman era and Early Middle Ages. It is recorded in several poetic and ba ...,Strathclyde Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...,Elmet Elmet ( cy, Elfed), sometimes Elmed or Elmete, was an independent Brittonic kingdom between about the 5th century and early 7th century, in what later became the smaller area of the West Riding of Yorkshire then West Yorkshire, South Yorkshir ...andGododdin The Gododdin () were a Brittonic people of north-eastern Britannia, the area known as the Hen Ogledd or Old North (modern south-east Scotland and north-east England), in the sub-Roman period. Descendants of the Votadini, they are best known a ..., whereOld Welsh Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...was also spoken. From the 8th century on, Wales was by far the largest of the three remnantBrythonic Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to: *Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain *Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic *Britons (Celtic people) The Br ...areas in Britain, the other two being the Hen Ogledd andCornwall Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ....

Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

in northwest Wales and Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

in east Wales. Gwynedd was the most powerful of these kingdoms in the 6th century and 7th century, under rulers such as Maelgwn Gwynedd

Maelgwn Gwynedd ( la, Maglocunus; died c. 547Based on Phillimore's (1888) reconstruction of the dating of the ''Annales Cambriae'' (A Text).) was king of Gwynedd during the early 6th century. Surviving records suggest he held a pre-eminent position ...

(died 547) and Cadwallon ap Cadfan

Cadwallon ap Cadfan (died 634A difference in the interpretation of Bede's dates has led to the question of whether Cadwallon was killed in 634 or the year earlier, 633. Cadwallon died in the year after the Battle of Hatfield Chase, which Bede rep ...

(died 634/5), who in alliance with Penda of Mercia

Penda (died 15 November 655)Manuscript A of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' gives the year as 655. Bede also gives the year as 655 and specifies a date, 15 November. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology and History'', 1934) put forward the theor ...

was able to lead his armies as far as Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

in 633, defeat the local ruler Edwin

The name Edwin means "rich friend". It comes from the Old English elements "ead" (rich, blessed) and "ƿine" (friend). The original Anglo-Saxon form is Eadƿine, which is also found for Anglo-Saxon figures.

People

* Edwin of Northumbria (die ...

and control it for approximately one year. When Cadwallon was killed in battle by Oswald of Northumbria

Oswald (; c 604 – 5 August 641/642Bede gives the year of Oswald's death as 642, however there is some question as to whether what Bede considered 642 is the same as what would now be considered 642. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology an ...

, his successor Cadafael ap Cynfeddw Cadafael ap Cynfeddw ( en, Cadafael son of Cynfeddw) was King of Gwynedd (reigned 634 – c. 655). He came to the throne when his predecessor, King Cadwallon ap Cadfan, was killed in battle, and his primary notability is in having gained the di ...

also allied himself with Penda against Northumbria, but thereafter Gwynedd, like the other Welsh kingdoms, was mainly engaged in defensive warfare against the growing power of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

.

Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

as the easternmost of the major kingdoms of Wales came under the most pressure from the English in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, Shropshire and Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

. This kingdom originally extended east into areas now in England, and its ancient capital, Pengwern

Pengwern was a Brythonic settlement of sub-Roman Britain situated in what is now the English county of Shropshire, adjoining the modern Welsh border. It is generally regarded as being the early seat of the kings of Powys before its establishm ...

, has been variously identified as modern Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

or a site north of Baschurch

Baschurch is a large village and civil parish in Shropshire, England.

It lies in North Shropshire, north-west of Shrewsbury. The village has a population of 2,503 as of the 2011 census. The village has strong links to Shrewsbury to the south-e ...

. These areas were lost to the kingdom of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

. The construction of the earthwork known as Offa's Dyke

Offa's Dyke ( cy, Clawdd Offa) is a large linear earthwork that roughly follows the border between England and Wales. The structure is named after Offa, the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia from AD 757 until 796, who is traditionally believed to h ...

(usually attributed to Offa

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of Æt ...

, King of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

in the 8th century) may have marked an agreed border.

For a single man to rule the whole country during this period was rare. This is often ascribed to the inheritance system practised in Wales. All sons received an equal share of their father's property (including illegitimate sons), resulting in the division of territories. However, the Welsh laws

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 20 ...

prescribe this system of division for land in general, not for kingdoms, where there is provision for an ''edling'' (or heir) to the kingdom to be chosen, usually by the king. Any son, legitimate or illegitimate, could be chosen as edling and there were frequently disappointed candidates prepared to challenge the chosen heir.

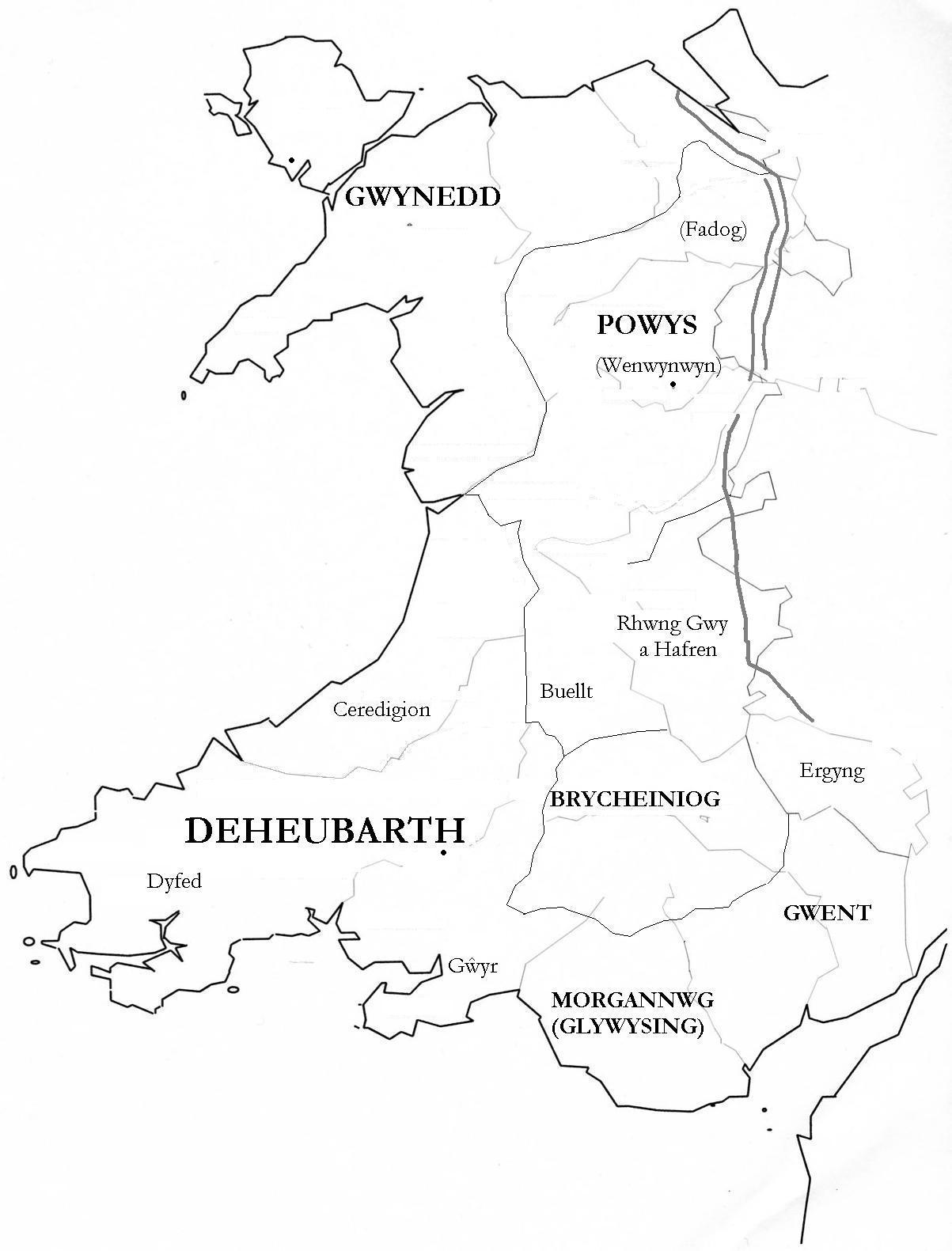

The first to rule a considerable part of Wales was Rhodri Mawr

Rhodri ap Merfyn ( 820 – 873/877/878), popularly known as Rhodri the Great ( cy, Rhodri Mawr), succeeded his father, Merfyn Frych, as King of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd in 844. Rhodri annexed Kingdom of Powys, Powys c. 856 and Seisyllwg c. 8 ...

(Rhodri The Great), originally king of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

during the 9th century, who was able to extend his rule to Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

and Ceredigion

Ceredigion ( , , ) is a county in the west of Wales, corresponding to the historic county of Cardiganshire. During the second half of the first millennium Ceredigion was a minor kingdom. It has been administered as a county since 1282. Cere ...

. Upon his death, his realms were divided between his sons. Rhodri's grandson, Hywel Dda

Hywel Dda, sometimes anglicised as Howel the Good, or Hywel ap Cadell (died 949/950) was a king of Deheubarth who eventually came to rule most of Wales. He became the sole king of Seisyllwg in 920 and shortly thereafter established Deheubarth ...

(Hywel the Good), formed the kingdom of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House of ...

by joining smaller kingdoms in the southwest and had extended his rule to most of Wales by 942. He is traditionally associated with the codification of Welsh law

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 2022 ...

at a council which he called at Whitland

Whitland (Welsh: , lit. "Old White House", or ''Hendy-gwyn ar Daf'', "Old White House on the River Tâf", from the medieval ''Ty Gwyn ar Daf'') is both a town and a community in Carmarthenshire, Wales.

Description

The Whitland community is ...

, the laws from then on usually being called the "Laws of Hywel". Hywel followed a policy of peace with the English. On his death in 949 his sons were able to keep control of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House of ...

but lost Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

to the traditional dynasty of this kingdom.

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raiders, particularly Danish raids in the period between 950 and 1000. According to the chronicle ''Brut y Tywysogion

''Brut y Tywysogion'' ( en, Chronicle of the Princes) is one of the most important primary sources for Welsh history. It is an annalistic chronicle that serves as a continuation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. ''Bru ...

'', Godfrey Haroldson carried off two thousand captives from Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

in 987, and the king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain

Maredudd ab Owain (died ) was a 10th-century king in Wales of the High Middle Ages. A member of the House of Dinefwr, his patrimony was the kingdom of Deheubarth comprising the southern realms of Dyfed, Ceredigion, and Brycheiniog. Upon the d ...

is reported to have redeemed many of his subjects from slavery by paying the Danes a large ransom.

Geography

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless moor

Moor or Moors may refer to:

Nature and ecology

* Moorland, a habitat characterized by low-growing vegetation and acidic soils.

Ethnic and religious groups

* Moors, Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta during ...

s and heath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a cooler ...

, and having large areas with peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

deposits. There is approximately of coastline and some 50 offshore islands, the largest of which is Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

. The present climate is wet and maritime

Maritime may refer to:

Geography

* Maritime Alps, a mountain range in the southwestern part of the Alps

* Maritime Region, a region in Togo

* Maritime Southeast Asia

* The Maritimes, the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Princ ...

, with warm summers and mild winters, much like the later medieval climate, though there was a significant change to cooler and much wetter conditions in the early part of the era.The same change in climate was occurring around the entire North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

perphery at this time. See Higham's ''Rome, Britain and the Anglo-Saxons'' (, 1992): cooler, wetter climate and abandonment of British uplands and marginal lands; Berglund's ''Human impact and climate changes—synchronous events and a causal link?'' in "Quaternary International", Vol. 105 (2003): Scandinavia, 500AD wetter and rapidly cooling climate and the retreat of agriculture; Ejstrud's ''The Migration Period, Southern Denmark and the North Sea'' (, 2008): p28, from the 6th century onwards farmlands in Denmark and Norway were abandoned; Issar's ''Climate changes during the holocene and their impact on Hydrological systems'' (, 2003): water level rise along NW coast of Europe, wetter conditions in Scandinavia and retreat of farming in Norway after 400, cooler climate in Scotland; Louwe Kooijmans' ''Archaeology and Coastal Change in the Netherlands'' (in Archaeology and Coastal Change, 1980): rising water levels along the NW coast of Europe; Louwe Kooijmans' ''The Rhine/Meuse Delta'' (PhD thesis, 1974): rising water levels along the NW coast of Europe, and in the Fens and Humber Estuary. Abundant material from other sources portrays the same information. The southeastern coast was originally a wetland, but reclamation has been ongoing since the Roman era.

There are deposits of gold, copper, lead, silver and zinc, and these have been exploited since the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

, especially so in the Roman era. In the Roman era some granite was quarried, as was slate in the north and sandstone in the east and south.

Native fauna included large and small mammals, such as the brown bear, wolf, wildcat, rodents, several species of weasel, and shrews, voles and many species of bat. There were many species of birds, fish and shellfish.

The early medieval human population has always been considered relatively low in comparison to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, but efforts to reliably quantify it have yet to provide widely acceptable results.

Subsistence

Much of the arable land is in the south, southeast, southwest, on Anglesey, and along the coast. However, specifying the ancient usage of land is problematic in that there is little surviving evidence on which to base the estimates. Forest clearance has taken place since the Iron Age, and it is not known how the ancient people of Wales determined the best use of the land for their particular circumstances, such as in their preference for wheat, oats, rye or barley depending on rainfall, growing season, temperature and the characteristics of the land on which they lived. Anglesey is the exception, historically producing more grain than any other part of Wales. Animal husbandry included the raising of cattle, pigs, sheep and a lesser number of goats. Oxen were kept for ploughing, asses for beasts of burden and horses for human transport. The importance of sheep was less than in later centuries, as their extensive grazing in the uplands did not begin until the thirteenth century. The animals were tended by swineherds and herdsmen, but they were not confined, even in the lowlands. Instead open land was used for feeding, and seasonaltranshumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower vall ...

was practised. In addition, bees were kept for the production of honey.

Society

Kindred family

The importance of blood relationships, particularly in relation to birth and noble descent, was heavily stressed in medieval Wales. Claims of dynastic legitimacy rested on it, and an extensive patrilinear genealogy was used to assess fines and penalties under Welsh law. Different degrees of blood relationship were important for different circumstances, all based upon the ''cenedl'' (kindred). The nuclear family (parents and children) was especially important, while the ''pencenedl'' (head of the family within four patrilinear generations) held special status, representing the family in transactions and having certain unique privileges under the law. Under extraordinary circumstances the genealogical interest could be stretched quite far: for the serious matter of homicide, all of the fifth cousins of a kindred (the seventh generation: the patrilinear descendants of a common great-great-great-great-grandfather) were ultimately liable for satisfying any penalty.Land and political entities

The Welsh referred to themselves in terms of their territory and not in the sense of a tribe. Thus there was ''Gwenhwys'' (" Gwent" with a group-identifying suffix) and ''gwyr Guenti'' ("men of Gwent") and ''Broceniauc'' ("men ofBrycheiniog

Brycheiniog was an independent kingdom in South Wales in the Early Middle Ages. It often acted as a buffer state between England to the east and the south Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth to the west. It was conquered and pacified by the Normans be ...

"). Welsh custom contrasted with many Irish and Anglo-Saxon contexts, where the territory was named for the people living there (Connaught for the Connachta, Essex for the East Saxons). This is aside from the origin of a territory's name, such as in the custom of attributing it to an eponymous founder (Glywysing

Glywysing was, from the sub-Roman period to the Early Middle Ages, a petty kingdom in south-east Wales. Its people were descended from the Iron Age tribe of the Silures, and frequently in union with Gwent, merging to form Morgannwg.

Name a ...

for ''Glywys'', Ceredigion

Ceredigion ( , , ) is a county in the west of Wales, corresponding to the historic county of Cardiganshire. During the second half of the first millennium Ceredigion was a minor kingdom. It has been administered as a county since 1282. Cere ...

for ''Ceredig'').

The Welsh term for a political entity was ''gwlad'' ("country") and it expressed the notion of a "sphere of rule" with a territorial component. The Latin equivalent seems to be ''regnum'', which referred to the "changeable, expandable, contractable sphere of any ruler's power". Rule tended to be defined in relation to a territory that might be held and protected, or expanded or contracted, though the territories themselves were specific pieces of land and not synonyms for the ''gwlad''.

Throughout the Middle Ages the Welsh used a variety of words for rulers, with the specific words used varying over time, and with literary sources generally using different terms than annalistic ones. Latin language texts used Latin language terms while vernacular texts used Welsh terms. Not only did the specific terms vary, the meaning of those specific terms varied over time as well. For example, ''brenin'' was one of the terms used for a king in the twelfth century. The earlier, original meaning of ''brenin'' was simply a person of status.

Kings are sometimes described as overkings, but the definition of what that meant is unclear, whether referring to a king with definite powers, or to ideas of someone considered to have high status.

Regional kingdoms

Dyfed

Dyfed () is a preserved county in southwestern Wales. It is a mostly rural area with a coastline on the Irish Sea and the Bristol Channel.

Between 1974 and 1996, Dyfed was also the name of the area's county council and the name remains in use f ...

is the same land of the Demetae

The Demetae were a Celtic people of Iron Age and Roman period, who inhabited modern Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in south-west Wales, and gave their name to the county of Dyfed.

Classical references

They are mentioned in Ptolemy's ''Geograp ...

shown on Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's map c. 150 during the Roman era. The fourth century arrival of Irish settlers intertwined the royal genealogies of Wales and Ireland, with Dyfed's rulers appearing in ''The Expulsion of the Déisi

''The Expulsion of the Déisi'' is a medieval Irish narrative of the Cycles of the Kings. It dates approximately to the 8th century, but survives only in manuscripts of a much later date. It describes the fictional history of the Déisi, a group ...

'', Harleian MS. 5389 and '' Jesus College MS. 20''. Its king Vortiporius

Vortiporius or Vortipor ( owl, Guortepir, Middle Welsh ''Gwrdeber'' or ''Gwerthefyr'') was a king of Dyfed in the early to mid-6th century. He ruled over an area approximately corresponding to modern Pembrokeshire, Wales. Records from this era a ...

was one of the kings condemned by Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

in his ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( la, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, sometimes just ''On the Ruin of Britain'') is a work written in Latin by the 6th-century AD British cleric St Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemning ...

'', c. 540. — in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

— English translation

While the better documented southeast shows a long and slow acquisition of property and power by the dynasty of Meurig ap Tewdrig Meurig ap Tewdrig (Latin: ''Mauricius''; English: ''Maurice'') was the son of Tewdrig (St. Tewdric), and a King of the early Welsh Kingdoms of Gwent and Glywysing. He is thought to have lived between 400AD and 600AD, but some sources give more spec ...

in connection with the kingdoms of Glywysing

Glywysing was, from the sub-Roman period to the Early Middle Ages, a petty kingdom in south-east Wales. Its people were descended from the Iron Age tribe of the Silures, and frequently in union with Gwent, merging to form Morgannwg.

Name a ...

, Gwent and Ergyng

Ergyng (or Erging) was a Welsh kingdom of the sub-Roman and early medieval period, between the 5th and 7th centuries. It was later referred to by the English as ''Archenfield''.

Location

The kingdom lay mostly in what is now western Herefordshir ...

, there is a near-complete absence of information about many other areas. The earliest known name of a king of Ceredigion

Ceredigion ( , , ) is a county in the west of Wales, corresponding to the historic county of Cardiganshire. During the second half of the first millennium Ceredigion was a minor kingdom. It has been administered as a county since 1282. Cere ...

was Cereticiaun, who died in 807, and none of the mid-Welsh kingdoms can be evidenced before the eighth century. There are mentions of Brycheiniog

Brycheiniog was an independent kingdom in South Wales in the Early Middle Ages. It often acted as a buffer state between England to the east and the south Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth to the west. It was conquered and pacified by the Normans be ...

and Gwrtheyrnion

Gwrtheyrnion or Gwerthrynion was a commote in medieval Wales, located in Mid Wales on the north side of the River Wye; its historical centre was Rhayader. It is said to have taken its name from the legendary king Vortigern ( cy, Gwrtheyrn). For ...

(near Buellt

Buellt or Builth was a cantref in medieval Wales, located west of the River Wye. Unlike most cantrefs, it was not part of any of the major Welsh kingdoms for most of its history, but was instead ruled by an autonomous local dynasty. During the No ...

) in that era, but for the latter it is difficult to say whether it had either an earlier or a later existence., ''Wales in the Early Middle Ages''

The early history in the north and east are somewhat better known, with Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

having a semi-legendary origin in the arrival of Cunedda

Cunedda ap Edern, also called Cunedda ''Wledig'' ( 5th century), was an important early Welsh people, Welsh leader, and the progenitor of the Royal dynasty of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd, one of the very oldest of western Europe.

Name

The n ...

from Manau Gododdin in the fifth century (an inscribed sixth century gravestone records the earliest known mention of the kingdom). Its king Maelgwn Gwynedd

Maelgwn Gwynedd ( la, Maglocunus; died c. 547Based on Phillimore's (1888) reconstruction of the dating of the ''Annales Cambriae'' (A Text).) was king of Gwynedd during the early 6th century. Surviving records suggest he held a pre-eminent position ...

was one of the kings condemned by Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

in his ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( la, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, sometimes just ''On the Ruin of Britain'') is a work written in Latin by the 6th-century AD British cleric St Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemning ...

'', c. 540. There may also have been sixth-century kingdoms in Rhos, Meirionydd

Meirionnydd is a coastal and mountainous region of Wales. It has been a kingdom, a cantref, a district and, as Merionethshire, a county.

Kingdom

Meirionnydd (Meirion, with -''ydd'' as a Welsh suffix of land, literally ''Land adjoined to Meirio ...

and Dunoding

Dunoding was an early sub-kingdom within the Kingdom of Gwynedd in north-west Wales that existed between the 5th and 10th centuries. According to tradition, it was named after Dunod, a son of the founding father of Gwynedd - Cunedda Wledig - wh ...

, all associated with Gwynedd.

The name of Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

is not certainly used before the ninth century, but its earlier existence (perhaps under a different name) is reasonably inferred by the fact that Selyf ap Cynan

Selyf ap Cynan or Selyf Sarffgadau (died 616) appears in Old Welsh genealogies as an early 7th-century King of Powys, the son of Cynan Garwyn.

His name is a Welsh form of Solomon, appearing in the oldest genealogies as Selim. He reputedly bore th ...

(d. 616) and his grandfather are in the Harleian genealogies

__NOTOC__

The Harleian genealogies are a collection of Old Welsh genealogies preserved in British Library, Harley MS 3859. Part of the Harleian Library, the manuscript, which also contains the ''Annales Cambriae'' (Recension A) and a version of th ...

as the family of the known later kings of Powys, and Selyf's father Cynan ap Brochwel appears in poems attributed to Taliesen

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Britons (Celtic people), Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the ''Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to h ...

, where he is described as leading successful raids throughout Wales. Seventh-century Pengwern

Pengwern was a Brythonic settlement of sub-Roman Britain situated in what is now the English county of Shropshire, adjoining the modern Welsh border. It is generally regarded as being the early seat of the kings of Powys before its establishm ...

is associated with the later Powys through the poems of ''Canu Heledd

''Canu Heledd'' (modern Welsh /'kani 'hɛlɛð/, the songs of Heledd) are a collection of early Welsh ''englyn''-poems. They are rare among medieval Welsh poems for being set in the mouth of a female character. One prominent figure in the poems i ...

'', which name sites from Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

to Dogfeiling

Dogfeiling was a minor sub-kingdom and later a commote in north Wales.

It formed part of the eastern border of the Kingdom of Gwynedd in early medieval Wales. The area was named for Dogfael, one of the sons of the first King of Gwynedd, Cunedda ...

to Newtown in lamenting the demise of Pengwern's king Cynddylan Cynddylan (Modern Welsh pronunciation: /kən'ðəlan/), or Cynddylan ap Cyndrwyn was a seventh-century Prince of Powys associated with Pengwern. Cynddylan is attested only in literary sources: unlike many kings from Brittonic post-Roman Britain, he ...

; but the poem's geography probably reflects the time of its composition, around the ninth or tenth century rather that Cynddylan's own time.

Kingship

Wales in the early Middle Ages was a society with a landed warrior aristocracy, and after c. 500 Welsh politics were dominated by kings with territorial kingdoms. The legitimacy of the kingship was of paramount importance, the legitimate attainment of power was by dynastic inheritance or military proficiency. A king had to be considered effective and be associated with wealth, either his own or by distributing it to others, and those considered to be at the top level were required to have wisdom, perfection, and a long reach. Literary sources stressed martial qualities such as military capability, bold horsemanship, leadership, the ability to extend boundaries and to make conquests, along with an association with wealth and generosity. Clerical sources stressed obligations such as respect for Christian principles, providing defence and protection, pursuing thieves and imprisoning offenders, persecuting evildoers, and making judgements. The relationship among people that is most appropriate to the warrior aristocracy is clientship and flexibility, and not one of sovereignty or absolute power, nor necessarily of long duration. Prior to the tenth century, power was held on a local level, and the limits of that power varied by region. There were at least two restraints on the limits of power: the combined will of the ruler's people (his "subjects"), and the authority of the Christian church., ''Wales in the Early Middle Ages''. There is little to explain the meaning of "subject" beyond noting that those under a ruler owed an assessment (effectively, taxes) and military service when demanded, while they were owed protection by the ruler.Kings

For much of the early medieval period kings had few functions except military ones. Kings made war and gave judgements (in consultation with local elders) but they did not govern in any sense of that word. From the sixth to the eleventh centuries the king moved about with an armed, mounted warband, a personal military retinue called a ''teulu'' that is described as a "small, swift-moving, and close-knit group". This military elite formed the core of any larger army that might be assembled. The relationships among the king and the members of his warband were personal, and the practice offosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by th ...

strengthened those personal bonds.

Aristocracy

Power was held at a local level by families who controlled the land and the people who lived on that land. They are differentiated legally by having a higher ''sarhaed'' (the penalty for insult) than the general populace, by the records of their transactions (such as land transfers) by their participation in local judgements and administration, and by their consultative role in judgements made by the king. References to the social stratification that defines an aristocracy are widely found in Welsh literature and law. A man's privilege was assessed in terms of his ''braint'' (status), of which there were two kinds (birth and office), and in terms of his superior's importance. Two men might each be an ''uchelwr'' (high man), but a king is higher than a ''breyr'' (a regional leader), so legal compensation for the loss to a king's bondsman (''aillt'') was higher than the equivalent loss to the bondsman of a ''breyr''. Early sources stressed birth and function as the determinators of nobility, and not by the factor of wealth that later became associated with an aristocracy.Populace

The populace included a hereditary tenant peasantry who were not slaves or serfs, but were less than free. ''Gwas'' ("servant", boy) referred to a dependent in perpetual servitude, but who was not bound to labour service (i.e., serfdom). Nor can the person be considered avassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. W ...

except perhaps as a clerical self-description, as in the 'vassal of a saint'. The early existence of the concept suggests a stratum of bound dependents in the post-Roman era. The proportion of the medieval population that consisted of freemen or free peasant proprietors is undetermined, even for the pre-Conquest period.

Slavery existed in Wales as it did elsewhere throughout the era. Slaves were in the bottom stratum of society, with hereditary slavery more common than penal slavery. Slaves might form part of the payment in a transaction made between those of higher rank. It was possible for them to buy their freedom, and an example of manumission at Llandeilo Fawr

Llandeilo () is a town and Community (Wales), community in Carmarthenshire, Wales, situated at the crossing of the River Towy by the A483 road, A483 on a 19th-century stone bridge. Its population was 1,795 at the 2011 Census. It is adjacent to ...

is given in a ninth-century ''marginalia'' note of the ''Lichfield Gospels

The Lichfield Gospels (recently more often referred to as the St Chad Gospels, but also known as the Book of Chad, the Gospels of St Chad, the St Teilo Gospels, the Llandeilo Gospels, and variations on these) is an 8th-century Insular Gospel ...

''. Their relative numbers is a matter of guess and conjecture.

Christianity

The religious culture of Wales was overwhelmingly Christian in the early Middle Ages. Pastoral care of the laity was necessarily rural in Wales, as it was in other Celtic regions. In Wales the clergy consisted of monks, orders and non-monastic clergy, all appearing in different periods and in different contexts. There were three major orders consisting of bishops (''episcopi''), priests (''presbyteri'') and deacons, as well as several minor ones. Bishops had some temporal authority, but not necessarily in the sense of a full diocese.Communities

Monasticism is known in Britain in the fifth century though its origins are obscure. The Church seemed episcopally dominated and largely consisting of monasteries. The size of the religious communities is unknown (Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

and the Welsh Triads

The Welsh Triads ( cy, Trioedd Ynys Prydein, "Triads of the Island of Britain") are a group of related texts in medieval manuscripts which preserve fragments of Welsh folklore, mythology and traditional history in groups of three. The triad is a ...

suggest they were large, the ''Lives of the Saints'' suggest they were small, but these are not considered credible sources on the matter). The different communities were pre-eminent within small spheres of influence (''ie'', within physical proximity of the communities). The known sites are mostly coastal, situated on good land. There are passing references to monks and monasteries in the sixth century (for example, Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

said that Maelgwn Gwynedd

Maelgwn Gwynedd ( la, Maglocunus; died c. 547Based on Phillimore's (1888) reconstruction of the dating of the ''Annales Cambriae'' (A Text).) was king of Gwynedd during the early 6th century. Surviving records suggest he held a pre-eminent position ...

had originally intended to be a monk). From the seventh century onward there are few references to monks but more frequent references to 'disciples'.

Institutions

Archaeological evidence consists partly of the ruined remains of institutions, and in finds of inscriptions and the long cyst burials that are characteristic of post-Roman Christian Britons. The records of transactions and legal references provide information on the status of the clergy and its institutions. Landed proprietorship was the basis of support and income for all clerical communities, exploiting agriculture (crops), herding (sheep, pigs, goats), infrastructure (barns, threshing floors), and employing stewards to supervise the labour. Lands that were not adjacent to the communities provided income in the form of (in effect) a business of landlordship. Lands under clerical proprietorship were exempt from the fiscal demands of kings and secular lords. They had the power of ''nawdd'' (protection, as from legal process) and were ''noddfa'' (a "''nawdd'' place" or sanctuary). Clerical power was moral and spiritual, and this was sufficient to enforce recognition of their status and to demand compensation for any infringement on their rights and privileges.Bede's ''Ecclesiastical History''

The notion of a separate Anglo-Saxon and British approach to Christianity dates back at least toBede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

. He portrayed the Synod of Whitby

In the Synod of Whitby in 664, King Oswiu of Northumbria ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Rome rather than the customs practiced by Irish monks at Iona and its satellite ins ...

(in 664) as a set-piece battle between competing Celtic and Roman religious interests. While the synod was an important event in the history of England and brought finality to several issues in Anglo-Saxon Britain, Bede probably overemphasised its significance so as to stress the unity of the English Church.

Bede's characterisation of Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

's meeting with seven British bishops and the monks of Bangor Is Coed (in 602–604) portrays the bishop of Canterbury as chosen by Rome to lead in Britain, while portraying the British clergy as being in opposition to Rome. He then adds a prophecy that the British church would be destroyed. His apocryphal prophecy of destruction is quickly fulfilled by the massacre of the Christian monks at Bangor Is Coed by the Northumbrians (c. 615), shortly after the meeting with Saint Augustine. Bede describes the massacre immediately following his delivery of the prophecy.

'Celtic' vs. 'Roman' myth

One consequence of theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

and subsequent ethnic and religious discord in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

was the promotion of the idea of a 'Celtic' church that was different from and at odds with the 'Roman' church, and that held to certain offensive customs, especially in the dating of Easter, the tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

, and the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

. Scholars have noted the partisan motives and inaccuracy of the characterisation, as has ''The Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

'', which also explains that the Britons using the 'Celtic Rite' in the early Middle Ages were in communion with Rome.

Cymry: Welsh identity forms

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic ( cy, Brythoneg; kw, Brythonek; br, Predeneg), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

It is a form of Insular Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic, a ...

''combrogi'', meaning "fellow-countrymen". It appears in '' Moliant Cadwallon'' (''In Praise of Cadwallon''), a poem written by Cadwallon ap Cadfan

Cadwallon ap Cadfan (died 634A difference in the interpretation of Bede's dates has led to the question of whether Cadwallon was killed in 634 or the year earlier, 633. Cadwallon died in the year after the Battle of Hatfield Chase, which Bede rep ...

's bard Afan Ferddig c. 633, and probably came into use a self-description before the seventh century. Historically the word applies to both the Welsh and the Brythonic-speaking peoples of northern England and southern Scotland, the peoples of the Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population spo ...

, and emphasises a perception that the Welsh and the "Men of the North" were one people, exclusive of all others. Universal acceptance of the term as the preferred written one came slowly in Wales, eventually supplanting the earlier ''Brython'' or ''Brittones''. The term was not applied to the Cornish people

The Cornish people or Cornish ( kw, Kernowyon, ang, Cornƿīelisċ) are an ethnic group native to, or associated with Cornwall: and a recognised national minority in the United Kingdom, which can trace its roots to the ancient Britons w ...

or the Bretons

The Bretons (; br, Bretoned or ''Vretoned,'' ) are a Celts, Celtic ethnic group native to Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, par ...

, who share a similar heritage, culture and language with the Welsh and the Men of the North. Rhys adds that the Bretons sometimes give the simple ''brô'' the sense of compatriot.

All of the ''Cymry'' shared a similar language, culture and heritage. Their histories are stories of warrior kings waging war, and they are intertwined in a way that is independent of physical location, in no way dissimilar to the way that the histories of neighboring Gwynedd and Powys are intertwined. Kings of Gwynedd campaigned against Brythonic opponents in the north.

Sometimes the kings of different kingdoms acted in concert, as is told in the literary ''Y Gododdin

''Y Gododdin'' () is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Brittonic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia at a p ...

''. Much of the early Welsh poetry and literature was written in the Old North by northern ''Cymry''.

All of the northern kingdoms and people were eventually absorbed into the kingdoms of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, and their histories are now mostly a footnote in the histories of those later kingdoms, though vestiges of the ''Cymry'' past are occasionally visible. In Scotland the fragmentary remains of the '' Laws of the Bretts and Scotts'' show Brythonic influence, and some of these were copied into the ''Regiam Majestatem

The ''Regiam Majestatem'' is the earliest surviving work giving a comprehensive digest of the Law of Scotland. The name of the document is derived from its first two words. It consists of four books, treating (1) civil actions and jurisdictions ...

'', the oldest surviving written digest of Scots law

Scots law () is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Ireland l ...

, where can be found the 'galnes' (''galanas

''Galanas'' in Welsh law was a payment made by a killer and his family to the family of his or her victim. It is similar to éraic in Ireland and the Anglo-Saxon weregild.

The compensation depended on the status of the victim, but could also be af ...

'') that is familiar to Welsh law

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 2022 ...

.

Irish settlement

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the Uí Liatháin

The Uí Liatháin (IPA: �iːˈlʲiəhaːnʲ were an early kingdom of Munster in southern Ireland. They belonged the same kindred as the Uí Fidgenti, and the two are considered together in the earliest sources, for example ''The Expulsion of th ...

and Laigin

The Laigin, modern spelling Laighin (), were a Gaelic population group of early Ireland. They gave their name to the Kingdom of Leinster, which in the medieval era was known in Irish as ''Cóiced Laigen'', meaning "Fifth/province of the Leinsterm ...

(with Déisi

The ''Déisi'' were a socially powerful class of peoples from Ireland that settled in Wales and western England between the ancient and early medieval period. The various peoples listed under the heading ''déis'' shared the same status in Gaeli ...

participation uncertain), arriving under unknown circumstances but leaving a lasting legacy especially in Dyfed

Dyfed () is a preserved county in southwestern Wales. It is a mostly rural area with a coastline on the Irish Sea and the Bristol Channel.

Between 1974 and 1996, Dyfed was also the name of the area's county council and the name remains in use f ...

. It is possible that they were invited to settle by the Welsh. There is no evidence of warfare, a bilingual regional heritage suggests peaceful coexistence and intermingling, and the ''Historia Brittonum

''The History of the Britons'' ( la, Historia Brittonum) is a purported history of the indigenous British (Brittonic) people that was written around 828 and survives in numerous recensions that date from after the 11th century. The ''Historia Bri ...

'' written c. 828 notes that a Welsh king had the power to settle foreigners and transfer tracts of land to them. That Roman-era regional rulers were able to exert such power is suggested by the Roman tolerance of native hill forts where there was local leadership under local law and custom. Whatever the circumstances, there is nothing known to connect these settlers either to Roman policy, or to the Irish raiders (the Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

) of classical Roman accounts.

Roman-era legacy

Forts and roads are the most visible physical signs of a past Roman presence, along with the coins and Roman-era Latin inscriptions that are associated with Roman military sites. There is a legacy ofRomanisation

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

along the coast of southeastern Wales. In that region are found the remains of ''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

s'' in the countryside. Caerwent

Caerwent ( cy, Caer-went) is a village and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located about five miles west of Chepstow and 11 miles east of Newport. It was founded by the Romans as the market town of ''Venta Silurum'', an important settle ...

and three small urban sites, along with Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

and Roman Monmouth, are the only "urbanised" Roman sites in Wales. This region was placed under Roman civil administration (''civitates

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on th ...

'') in the mid-second century, with the rest of Wales being under military administration throughout the Roman era. There are a number of borrowings from the Latin lexicon

A lexicon is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Koine Greek language, Greek word (), neuter of () ...

into Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

, and while there are Latin-derived words with legal meaning in popular usage such as ''pobl'' ("people"), the technical words and concepts used in describing Welsh law

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 2022 ...

in the Middle Ages are native Welsh, and not of Roman origin.

There is ongoing debate as to the extent of a lasting Roman influence being applicable to the early Middle Ages in Wales, and while the conclusions about Welsh history are important, Wendy Davies

Wendy Elizabeth Davies (born 1942) is an emeritus professor of history at University College London, England. Her research focuses on rural societies in early medieval Europe, focusing on the regions of Wales, Brittany and Iberia.

Career

Da ...

has questioned the relevance of the debates themselves by noting that whatever Roman provincial administration might have survived in places, it eventually became a new system appropriate to the time and place, and not a "hangover of archaic practices". ''Patterns of Power in Early Wales''

See also

*Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the list of legendary kings of Britain, legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It ...

*Medieval Welsh literature

Medieval Welsh literature is the literature written in the Welsh language during the Middle Ages. This includes material starting from the 5th century AD, when Welsh was in the process of becoming distinct from Common Brittonic, and continuing t ...

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales pages on Early Middle Ages

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wales In The Early Middle Ages .01 Sub-Roman Britain

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...